Daniel Story on Technology, Art, and the Philosophy of Loss

What if technology could help us reimagine our relationship with death? Daniel Story, a philosophy professor at California Polytechnic State University, is exploring this very question through his work on „chatbots of the dead“—AI tools designed to represent deceased individuals. In collaboration with artist Amy Kurzweil, Daniel challenges dystopian perspectives, instead presenting these chatbots as creative representations, akin to memoirs or theater, that prompt reflection and emotional connection.

In this interview, Daniel discusses the ethical challenges, artistic possibilities, and risks of this emerging technology. With a philosophical lens, he invites us to consider how these tools could reshape mourning, memory, and how we connect with the past.

QUEST: Thank you for joining us today, Daniel. Could you start by introducing your background and how you became interested in the ethics of AI and emerging technologies?

Daniel Story: Thanks for having me! I’m an assistant professor of philosophy at California Polytechnic State University. I got my PhD at UC Santa Barbara, where I focused mostly on ethics, and particularly shared agency, which refers to people doing things together. More recently, I’ve become interested in topics in the philosophy of death and the ethics of technology. These interests intersect in the project I’m going to talk about today, which focuses on chatbots that represent dead people. One of my deepest philosophical convictions is that we in the West have an impoverished relationship with death, and one thing that’s exciting about technologies of death, like chatbots of the dead, is that they can help us engage with our mortality in ways that promote flourishing, if they’re used thoughtfully.

QUEST: Your project with artist Amy Kurzweil focuses on chatbots of the dead. How did this collaboration

begin, and what are you exploring?

Daniel Story: Amy is not only an artist but a very philosophical and intellectual person. We’re close friends, and we talk a lot about philosophy and literature and that sort of thing. We have this weird connection where we somehow talk and think about things in similar ways, despite our different backgrounds.

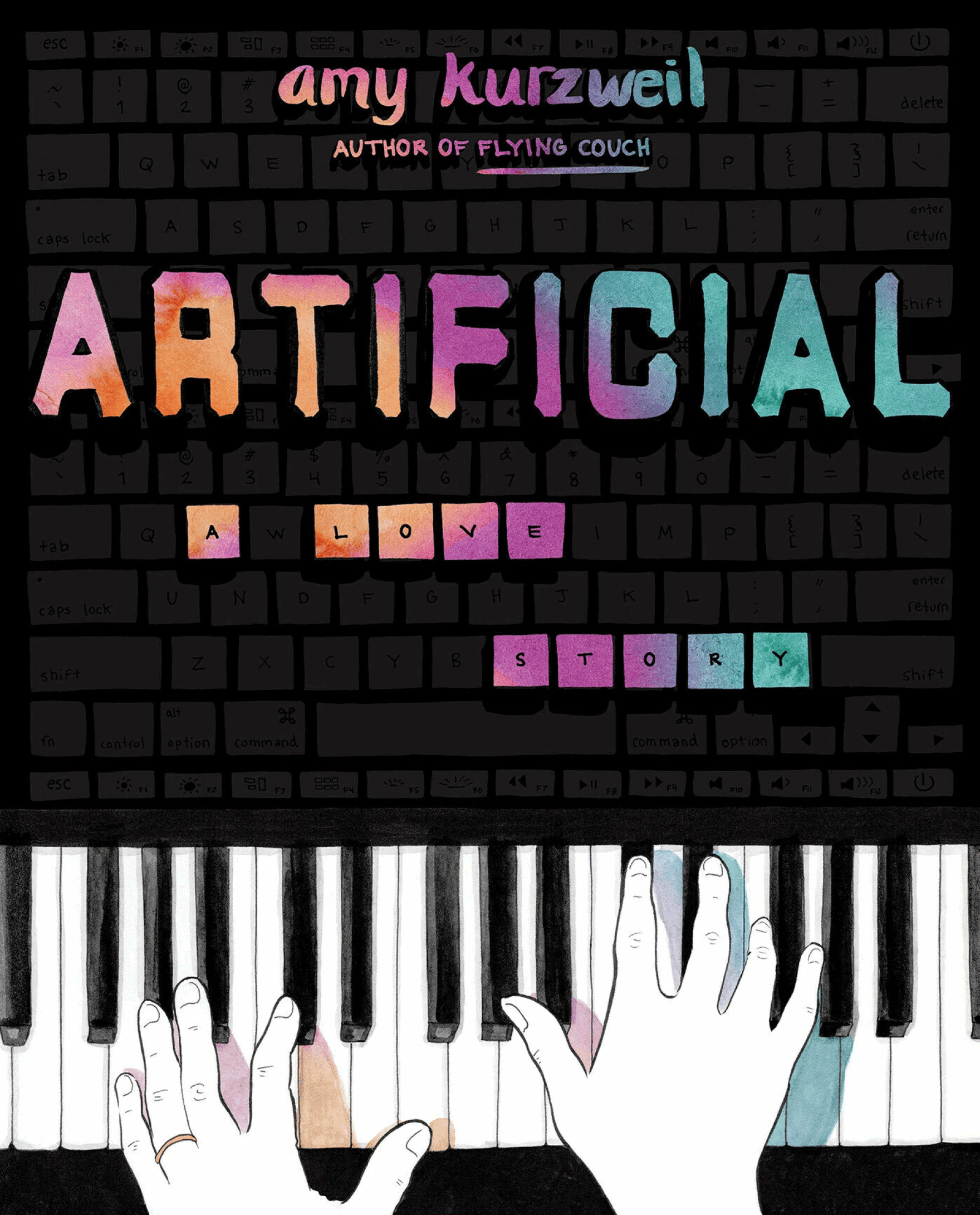

Winner of the Living Now Book Award

Finalist for the American Book Fest Best Book Awards

A visionary story of three generations of artists whose search for meaning and connection transcends the limits of life.

How do we relate to—and hold—our family’s past? Is it through technology? Through spirit? Art, poetry, music? Or is it through the resonances we look for in ourselves?

In Artificial, we meet the Kurzweils, a family of creators who are preserving their history through unusual means. At the center is renowned inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil, who has long been saving the documents of his deceased father, Fredric, an accomplished conductor and pianist from Vienna who fled the Nazis in 1938.

Once, Fred’s life was saved by his art: an American benefactor, impressed by Fred’s musical genius, sponsored his emigration to the United States. He escaped just one month before Kristallnacht.

Now, Fred has returned. Through AI and salvaged writing, Ray is building a chatbot that writes in Fred’s voice, and he enlists his daughter, cartoonist Amy Kurzweil, to help him ensure the immortality of their family’s fraught inheritance.

Amy’s deepening understanding of her family’s traumatic uprooting resonates with the creative life she fights to claim in the present, as Amy and her partner, Jacob, chase jobs, and each other, across the country. Kurzweil evokes an understanding of accomplishment that centers conversation and connection, knowing and being known by others.

With Kurzweil’s signature humanity and humor, in boundarypushing, gorgeous handmade drawings, Artificial guides us through nuanced questions about art, memory, and technology, demonstrating that love, a process of focused attention, is what grounds a meaningful life.

Amy has been thinking about chatbots of the dead for much longer than me. Around 2018 or so, before we met, Amy participated in this shared project with her father Ray Kurzweil and others to create a chatbot based on her dead grandfather Fred, who Amy never met, using Fred’s letters and other personal documents. Amy wrote about this experience in her graphic memoir, *Artificial: A Love Story*. Naturally, this was a topic of conversation for us as Amy was working on her book. And so at some point we just thought: “Why not write some philosophy together?”

Our project isn’t about building a chatbot but developing a conceptual framework for thinking about how chatbots of the dead can be designed and used positively. One of our core goals is to push back against common dystopian ways of thinking about these phenomena, like the sort of thing we see in science fiction, such as the popular *Black Mirror* episode “Be Right Back,” which has set the tone for these discussions about chatbots of the dead.

QUEST: What personally draws you to this topic?

Daniel Story: Honestly, I’m fascinated by death because I fear it. Engaging with death through philosophy helps me process that fear. And Amy and I think that chatbots of the dead can be similarly helpful in processing fear and grief and loss. This is important because I think in the modern world we see an erosion of opportunities for this sort of thing.

QUEST: What specifically distinguishes your approach to chatbots of the dead from other approaches to understanding this technology?

Daniel Story: Chatbots constitute a very new way of representing someone. There aren’t yet settled ways of thinking about what these representations are or what they are for. Most people who envision chatbots of the dead imagine that they will function as a kind of replacement for deceased people, or as ersatz companions that fill the hole left by someone’s death. This is what causes people to worry about this technology. Amy and I think that way of envisioning this technology is wrongheaded. We think that chatbots should be thought of as artistic representations, which are similar to memoir, historical fiction, or interactive theater.

QUEST: Could you elaborate on how you see the artistic potential of chatbots of the dead, and what forms of creative expression they might enable?

Daniel Story: We think that chatbots of the dead function to structure and prompt imagination about deceased people. If you interact with a chatbot of someone you loved, you aren’t actually talking to your loved one, but you are having this imaginative experience whose content and structure is jointly determined by you and the chatbot. This isn’t so different from what happens when you read memoir, or go to the theater, or interact with an Elvis impersonator. We particularly like the theater analogy: we think that people should think about chatbots by analogy with actors. A chatbot is like an actor that is playing the role of your loved one in an interactive performance.

There are lots of advantages to conceptualizing chatbots of the dead in this way, both on the side of users and designers. This framework clarifies and

accentuates the relationship between chatbots and actors. Everyone knows that actors aren’t identical to the character they play. Actors represent those characters, and provide perspectives on them. Similarly, your chatbot isn’t identical to your loved one. Your chatbot represents them in this distinctive way, providing a perspective on them. And here’s where the design side comes in. Just as there are diverse acting perspectives, diverse ways an actor can play a character–ranging from “realistic,” to stylized, to wacky, to avant-garde–so there’s this huge chatbot design possibility space. There are many ways you might design a chatbot, all of which can be valuable. And people who are interested in this technology should explore this possibility space and draw inspiration from the arts, theater, memoir, and so on.

Illustration by Amy Kurzweil

QUEST: How do you think the widespread adoption of chatbots of the dead could impact traditional cultural practices related to mourning, remembrance, or even ideas about the afterlife?

Daniel Story: I’m not sure. It’s a big question. There are lots of traditional ideas and practices, such as beliefs in the afterlife or rituals for communicating with the dead, that provide a felt sense that the human community extends beyond death and sustain connections with people who are gone. But in many parts of the world these traditional ideas and practices are disappearing. And so maybe chatbots of the dead, properly conceived, can play the same sort of function, just like other forms of art, such as memoir.

QUEST: How could this technology help people connect with ancestors they never met, like grandparents?

Daniel Story: Well like I said this technology is a tool for imaginative engagement, which can provide a unique way of encountering someone’s legacy, learning about them, or getting a feel for what they were like. One of our ideas, though, is that, like a lot of art, the process of creating a chatbot is generally at least as valuable as the final product. To make a chatbot like this, you have to utilize archives of personal data and make lots of choices about how to use that data in the creative process to create the final representation. This in itself can be meaningful, and prompt reflection about the person, your relationship to them, and so on. This is something Amy discovered and documented in her book. And this is why we think that technology companies should provide users with the means to create their own chatbots of the dead rather than simply delivering pre-made chatbots to users.

QUEST: What are the potential risks and best outcomes of chatbots of the dead?

Daniel Story: There are lots of serious risks people talk about. One sort of worry is that emotionally vulnerable users might conflate their chatbot with the deceased. That can be problematic for all sorts of reasons. Another sort of worry relates to the fact that users might form one-sided emotional bonds, as chatbots can’t reciprocate feelings, and this is seen by some people to be problematic. There’s also the risk of commercial exploitation because companies might manipulate users’ attachment to make a profit. But we argue that if everyone conceptualizes chatbots as artistic representations rather than ambiguous replacements, that will mitigate these sorts of risks.

QUEST: This reminds me of how people used to get attached to Tamagotchis in the 90s. Do you think chatbots could create similar attachments?

Daniel Story: Definitely that’s a worry, that people could form unhealthy attachments. That’s why we’re developing a framework for designing chatbots of the dead in a way that reduces these risks. We don’t want the chatbot to replace real human connections, but rather to act as a tool for reflection and engagement with memory.

QUEST: I’m intrigued by your approach, especially as a professor of ethics. Do you think we can influence or regulate the development of these technologies?

Daniel Story: I’m not sure how much of an impact someone like Amy or me can have. This is a problem for all applied ethics, especially in contexts like this where there are strong market incentives pushing in different directions. Some suggest heavy regulation, like classifying chatbots of the dead as medical devices, but I don’t think that’s feasible. The technology is already widely available. Over time, society will adjust to these tools, just like we did with photography in the early 20th century. While there are legitimate concerns, I believe the solution lies more in education and digital literacy than in regulation.

QUEST: That’s an interesting point. As society adjusts, do you think we can foresee all the potential issues?

Daniel Story: Probably not. It’s going to be a bumpy road, but I’m optimistic that society will adapt inthe long term. In the short term, though, we need to be vigilant about all the potential disruptions and harms, especially when it comes to commercial exploitation.

QUEST: What about consent from the deceased? Do you think it’s necessary to have someone’s prior permission to create a chatbot of them after they die?

Daniel Story: I think it’s complicated. But in many cases, I do not think explicit consent is necessary, especially if the chatbot is understood to be a creative representation, not a stand-in for the person. We don’t always have to ask permission to write biographies or create historical fiction about someone who has died. And if we’re talking about a chatbot that isn’t used deceptively, but is openly portrayed as a kind of fictional representation of a real person, I don’t think there’s usually going to be an issue.

QUEST: That makes sense. One last question: Do you think these chatbots could ever develop real emotions or consciousness?

Daniel Story: Well I don’t know. Certainly not in the near future, but maybe it’s possible. Consciousness probably depends on how something functions, not what it’s made of. So, in theory, an AI could develop emotions or consciousness, though we’re still far from that point. For now, interactions with chatbots are in that sense one-sided.

Daniel Story is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Cal Poly, SLO and a Fellow at the Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group. Daniel obtained his PhD in Philosophy from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2020.

His research interests include shared agency, the philosophy of death, and the ethics of technology. Daniel’s research on shared agency focuses mostly on how acting together can lead to shared responsibility and moral luck. His research on death focuses mostly on death’s badness. His research on technology focuses mostly on the use of artificial intelligence to represent people.